Artist and musician Sasha Skochilenko has been jailed at Saint Petersburg’s Detention Center no. 5 since April. Suspected of “distributing fake news about the Russian army”, she is currently awaiting trial. Sasha faces up to ten years in prison for replacing price tags at a supermarket with anti-war messages. Her detention has been repeatedly extended in spite of her medical issues: the young woman is suffering from heartaches and problems connected to gluten intolerance.

What are the living conditions of women kept at the detention center on Arsenalnaya Street? How do they have open air time in a yard of two by five meters? Why do they have to wash themselves at the toilet? Is it allowed to sit on an upper bunk bed? On the 26th of June, Paperpaper.ru published Sasha’s notes about her first month in jail.

— I have lived at the DC-5 for a month now, and it’s about time to review my observations of this place. I decided to do such reviews at the end of each month of my being here. No one is letting me out anytime soon, so I’ll have an opportunity to tell a lot, so long as I have the privilege to do so, unlike most women at Arsenalnaya.

Most people here are annoyed about lots of things but terribly afraid to speak out, because they might be transferred to even worse conditions for complaining. Even if they do complain, more often than not the administration will ignore their pleas (unlike mine), and there is a uniform response to nearly every important question: “You’re not at a resort.” For instance: “Our radiator leaks, we have to put a container underneath so that it doesn’t ooze to the floor below, we change it every hour!” – “You’re not at a resort.” “Our ceiling is leaking, we spent half a night running around with buckets!” – “You’re not at a resort.”

Before I go on ranting about our beloved jail, I have to make a reservation: yes, all sorts of things happen here, but not everyone on the staff is to blame. There are humane and compassionate people who know that an inmate’s life isn’t easy as it is, and try not to make it harder for us. This article is not about those people.

How to take a shower

— So, let’s get back to our housing conditions that, remember, aren’t a resort: indeed, they are unsanitary. The buildings are quite rundown: squalor and cold reign, cobwebs hang from corners and fungus grows freely on walls and ceilings. The ceiling in our block’s shower room is black from mold. The shower room’s condition reminded some of my respondents of films about concentration camps. Luckily, the rusty, pipy overhead showers have running water, although it isn’t always hot.

In many cells there are bottles with water prepared in advance, in case of cuts in hot and cold water supply (that has happened during this month!). Showers at the infirmary, where I’m currently staying, are in much better condition, although black mold is still present. We are taken to shower twice a week, if we’re lucky and if there’s hot water.

Patriarchal society insists that women need to be scrupulous about their hygiene and must smell sweet: so, how do they wash themselves in this place? In the evening we fill half-liter bottles with water and “take a shower” by the toilet bowl.

It is an elaborate task. Try doing it at home. First, wash your crotch pouring water from the bottle (that’s an easy part), then try to wash your feet (more difficult), then your armpits (this, for me, still feels like a Fort Boyard kind of challenge), then change and wipe drops of water from the floor.

All of that needs to be done in 6 to 8 minutes if you are in a cell for eighteen people. In a cell for six you can afford 10 to 15 minutes. If you are in a double cell, then there is no time limit for your private time with a bottle (I am now in such a cell, thanks to the civil society).

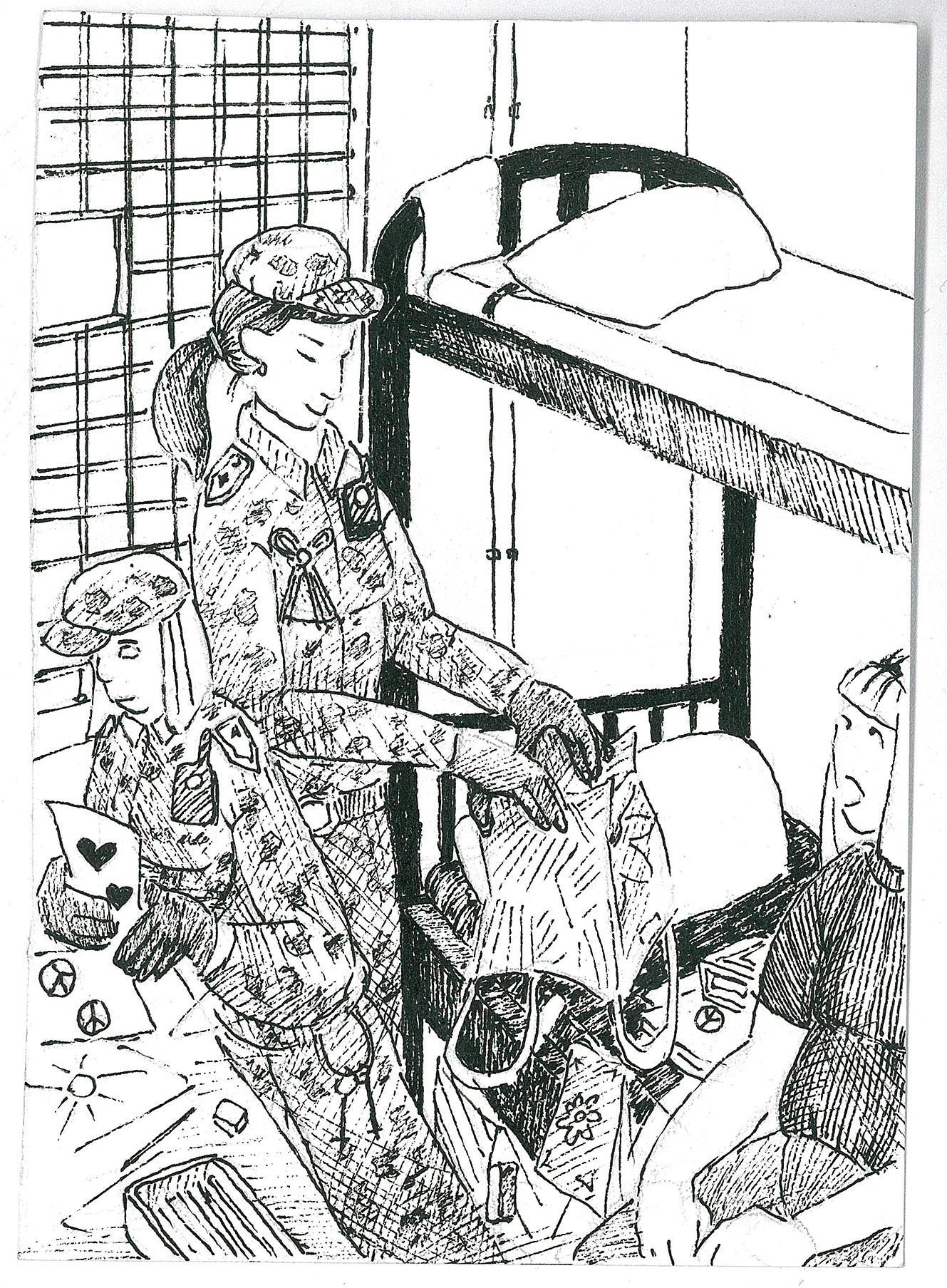

How to sit

— Many difficult questions arise inside a severely overcrowded cell. For instance: can you sit on your bed if you, as a fresh inmate, is designated an upper bunk? Within the jail community it is widely believed that only those occupying lower bunks have the right to sit on their beds. As a reason, people will usually cite precedent from experience with jail officers (“There was this one time when they threw out to the hallway all those sitting on upper bunks along with their mattresses”), or say that, if a guard suddenly walks in, people won’t have the time to come down and take the “hands behind back” position.

A guard in our unit explained to me that we would “wrinkle the linen” if we break the rule; however, neither the public human rights office nor the guard’s immediate superior agree with his opinion: both told me it was allowed to sit on one’s bed, even if it’s an upper bunk, after wakeup call.

Why am I making such a big deal out of a question that seems so silly? A crowded cell houses eighteen people in an area of 35 square meters. It would be interesting to know where to find the four meters per person guaranteed by prison regulations. In the toilet, perhaps? No. This space isn’t there, no matter how many statements the Federal Penitentiary Service issues to disprove it. In a cell like that, any small piece of usable surface will be fiercely contested, through no fault of the inmates. There is an unspoken rule in those cells that fresh inmates aren’t allowed to take a seat on someone else’s lower bunk, which makes their life a hard physical challenge, especially for elderly ladies.

In a kind of a “hazing ritual”, a fresher will have to move around the cell or only sit on a hard wooden bench for weeks or even months. Run an experiment: try to spend a day without lying down, sitting on a soft surface or going outside for more than an hour (you can’t really take a seat outside, either). Try doing that for a few days. How are you feeling and how is your back doing?

Taking a walk

— Now a few words about our time in the open air. I need to give credit to our jail and especially minor staff (who tend to be the most humane element of life inside): the right to spend an hour in the open air is never violated, and on some occasions the staff will even make an effort to extend this time. However, the conditions of our walks leave much to be desired.

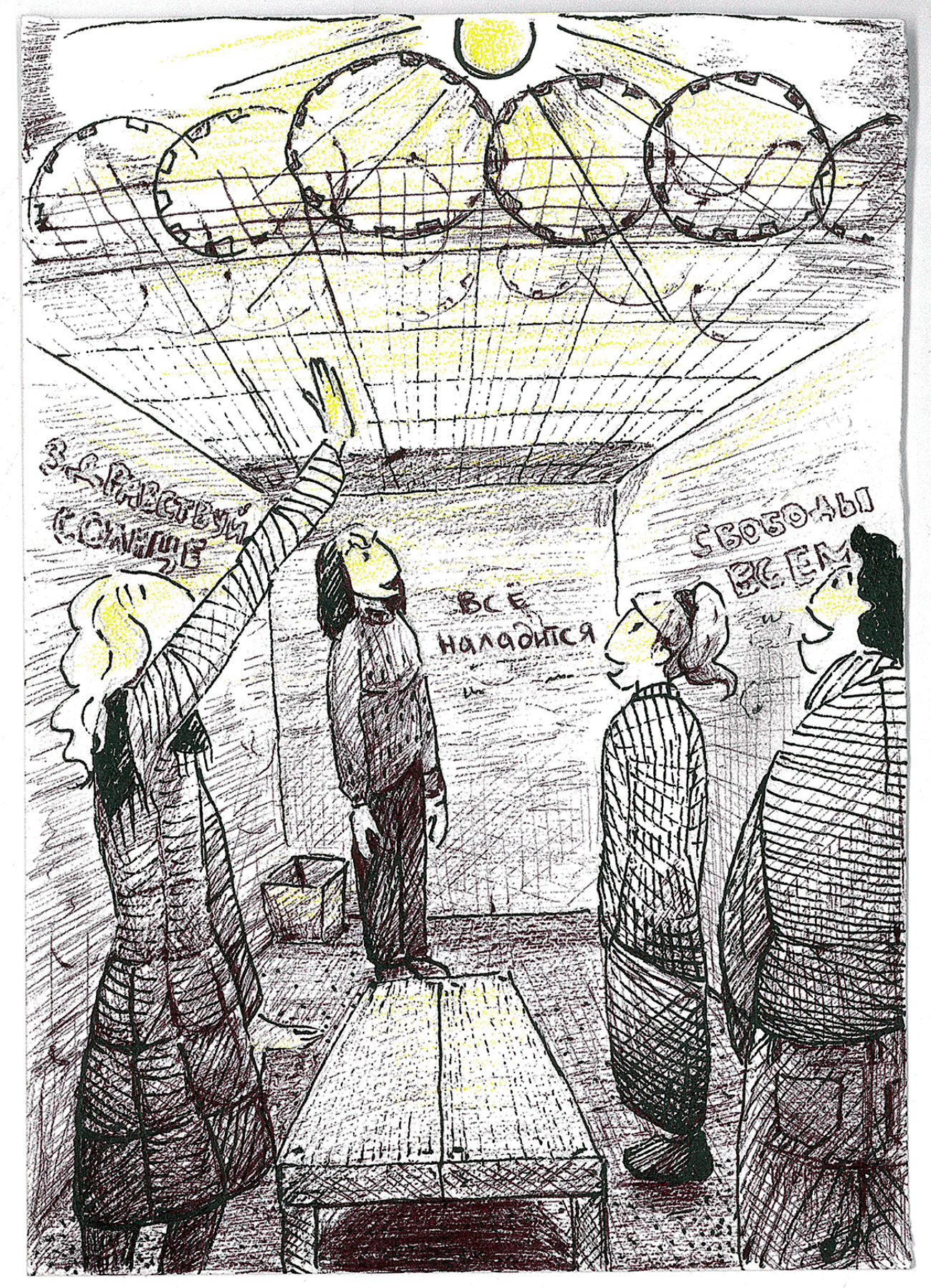

The open air space that I have now, together with my cellmate, feels like a paradise to me. It is a concrete box that has bars covered with barbed wire for a ceiling. The space is approximately three by five meters in size, it has a long bench and a small, rusty rain cap. Three dandelions pierce out through the crumbling concrete floor. I am very fond of them and I watch them grow little by little each day: these are the only plants I see during my open air time. I usually run around the yard, dance, sing, exercise and read aloud my poems.

And now let’s take a look at the yards where I went during my first two weeks. Those open air spaces are called “two by fives” in the jail lingo, referring to the exact size of the concrete boxes with random paint stains over peeling walls. Cigarette stubs are scattered on the floor in the corners, and there’s no vegetation except patches of moss growing near the ceiling bars wrapped in barbed wire. Now imagine 18 people at a yard of two by five meters in size with a dirty meter-long bench at the center. The “walking” amounts to slowly moving around in circles in the same direction, one after another. You can also linger in a corner, turning your face to the sun. That’s about it.

Many people in the jail hate me for complaining. The reason is, probably, that when I complain, everyone else gets scolded: guards, cellmates and, likely, superiors, as is evident from torrents of invective coming down the hierarchical ladder. On one occasion, an anonymous tall man wearing an officer’s uniform came running into our cell and started shouting at me: “Who’s doing all this complaining that reaches all the way to Moscow? The plumbing is just fine in the 17th cell! Yeah, the flute’s out of joint, yeah, the bowl leaks, but wait till you see a real prison with rats running around!”

I deeply appreciate this macho’s ambition to work at a real prison. But, with all due respect, a detention center is not a real prison: it’s a jail that houses people pending trial (although many inmates spend years in these conditions awaiting investigative action). The detention center’s purpose, as the establishment’s superior himself admitted to me, is to keep us from interfering with investigation and judgment, and to make sure we stay safe and secure.

It isn’t meant to punish us, no: many people inside aren’t proven guilty or their charge is quite arbitrary, and some even will leave the premises acquitted. And subjecting women who stay here to physical hardship and suffering is definitely not the purpose of a jail like this. Yes, a detention center isn’t a resort, but it’s not a labor camp, either, and it’s not supposed to have people do maintenance work on ancient plumbing that’s constantly leaking or make them pay for janitorial utensils (which must be supplied to every cell for free, according to the regulations). And certainly a jail is not a different kind of camp to have women suffer from inhumane conditions of detention.

It’s a shame that our jail is the only pretrial detention center for women in Saint Petersburg and the whole region. Modern facilities have been created at Kresty Detention Center for men. Here, on the other hand, the list of new and modern equipment is limited to a children’s playground and an ultrasound machine at the gynecological care room.

Thank you for reading this to the end: it is quite a long article! And yet there’s a lot more I would like to tell. I keep learning new things each day. Well, nobody’s letting me go anytime soon, so I’ll have ample time to follow up.

According to the Council of Europe’s 2021 report, there are 356 prisoners per 100,000 population in Russia (surpassed only by Turkey, at 357, compared to 45 prisoners in Iceland and 50 in Finland). Expenses on housing prisoners are the lowest in Russia: just 2,8 € per prisoner per day (Norway and Sweden spend about 300 € each, according to the report). Saint Petersburg and the surrounding Leningrad Oblast are among the top three Russian regions by the total sum of compensations paid by penal colonies for torture and humiliating housing conditions.

The official website of Detention Center no. 5 says that the jail boasts a library with 10,000 available books, an events hall with 120 seats, a gym, a volleyball court, a hair salon, and facilities for women who have children under three years old.

DC-5 hosts an annual Miss Arsenalnaya pageant. Contests include “Introduction”, “Defile”, “Talents”, “Lady Friend”, “Cooking Expert”, and “Handmade Dress”. Every contestant receives a ribbon, while “Miss Arsenalnaya 2021” was given a crown.

The pretrial jail’s management also runs a “Tasty Morsel” cooking contest and another competition named “Kind Hostess”. During the latter, women “display their needlework skills, solve logical problems and answer the jury’s questions about cooking.” On Women’s Day on the 8th of March, the DC-5 hosted a “Tender Wave beauty festival”: “twelve ‘experts’ created beautiful and original hairstyles and added makeup to complete the look.”

In the spring of 2022, according to the jail’s inmates, there was a major plumbing leakage at the jail, which prisoners themselves had to fix: they spent a night carrying buckets of water. In May, the same cell’s ceiling collapsed a few days after repair works. An inmate was reportedly hit by one of the collapsing pieces; the woman received a hip injury but the cell was kept in use. The incident was not officially reported.

Detention Center no. 5 on Arsenalnaya Street currently houses defendants in notable political cases. One of them is Belarusian Yana Pinchuk. She is accused of creating an “extremist” online chat in her home country and faces up to 19 years in prison. Pinchuk is under threat of extradition; Memorial Human Rights Center considers her a political prisoner.

The detention center’s prisoners charged with “distributing fake news” include Sasha Skochilenko, Olga Smirnova and Viktoria Petrova. Sasha and Olga are recognized as political prisoners by Memorial. Amnesty International also named Sasha prisoner of conscience.

Paperpaper.ru — is independent media from Saint-Petersburg, Russia. We’ve been reporting on the Russian-Ukrainian war since the day it started. As a result, our website was blocked by the Russian government.

For 10 years we’ve been writing about the local community, business and initiatives. Yet, our main goal was always to improve life in the city we love.

We are Russian-language media but now we translate our the most significant articles to share it with our English speaking audience. Help independent journalism — save the freedom of speech!