More than half of independent media readers still remain in Russia. Many not only have a negative view of the situation in the country but also suffer from it. Those who have left the country want to return after a political change but only few expect this to happen in the near future. And almost no one considers Russians to be politically hopeless.

On the anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Paperpaper.ru found out about the plans, work situation, and sentiments among independent media readers and, together with political scientist Margarita Zavadskaya, analyzed the results. Here are the conclusions of our study.

We collected over 3100 responses from readers of Paperpaper.ru, Paper Kartuli, Novaya Gazeta. Europe, and the Eyewitnesses Media Project. The data is not sufficient to make conclusions about all those remaining in Russia or all emigrants, but it reflects the mood of the audience of independent Russian-language media. The project was implemented by the research department of Paperpaper.ru, which has been conducting its own surveys and analyzing sociological data from other experts since 2016.

From this feature you will learn

How many people have left Russia

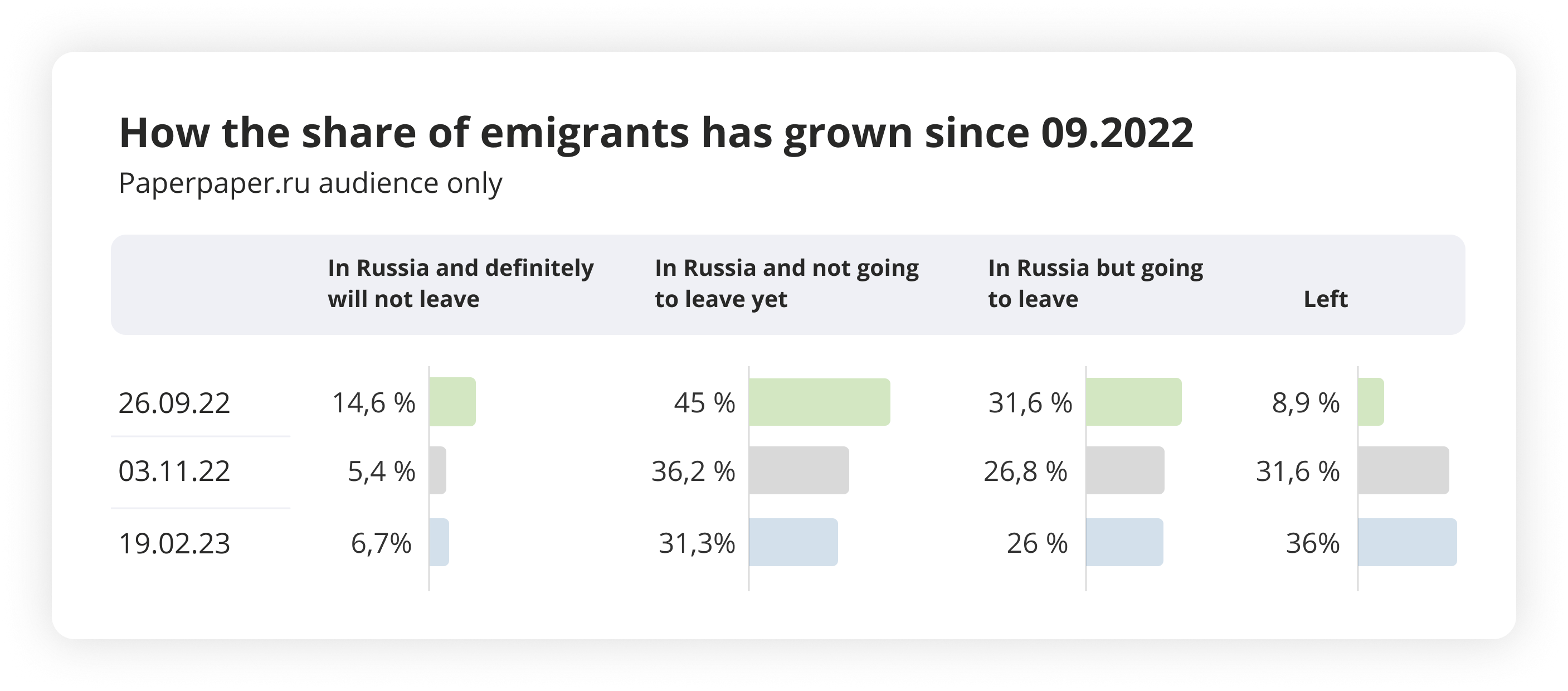

Сonclusion: The majority of readers remain in Russia. But the number of those who have left is growing.

More than half (57%) of the respondents remain in the country. However, every third person among those who remain stated that they plan to leave. Approximately 4% have not made a final decision yet and share their time between two places. In the analysis, we combined those who plan to leave and those who are splitting their time between two homes into the “undecided” category.

The number of those who left is much higher than it was at the end of September and the beginning of November: the last time when we asked Paperpaper.ru’s readers about it: now they make up 36% of our audience.

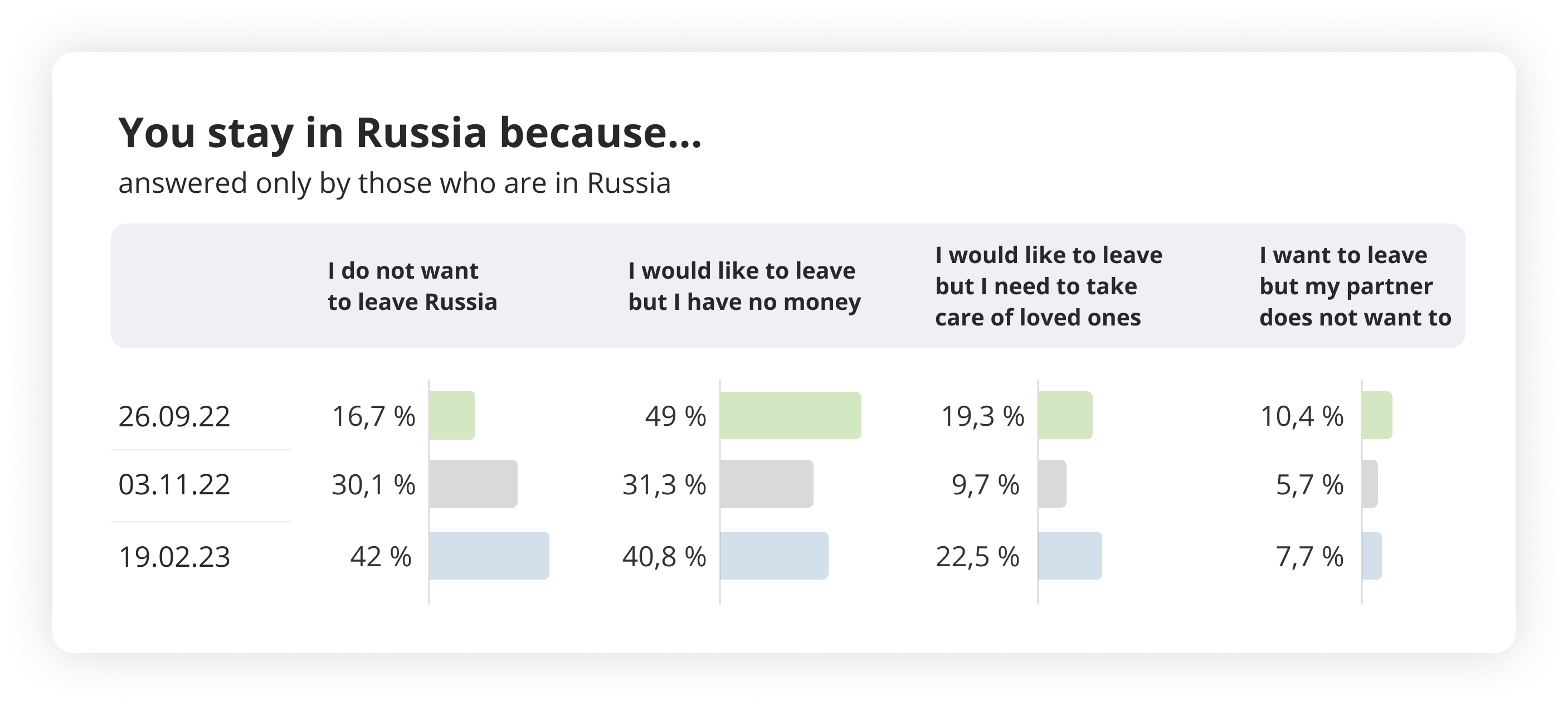

Conclusion: People are not leaving because of money, education, or family. But many just want to stay in Russia.

We asked independent media readers who remained in Russia if they wanted to leave and why they had stayed. 41% of respondents reported a lack of money for relocation, while every fifth person is motivated by the need to take care of their loved ones. Another common reason (12% of responses) is education, either for themselves or for their children. Nearly 8% (mostly women) complain that they would like to leave, but their partner is against it.

An impressive proportion, 42%, answered that they have no desire to leave. Moreover, in recent months, the number of such people has increased among those who remained. Presumably, some of those who previously wanted to but could not leave have since found an opportunity to do so, and now it is those who consciously want to stay in Russia has become larger.

Margareta Zavadskaia, Senior Research Fellow at the Finnish Institute of International Affairs and a researcher at the OutRush group says:

- “A high percentage of those who do not want to leave is interesting. Among those who stayed, a heroic narrative may have formed: “I stay to live” or “I am not backing out.”

- According to our observations [at OutRush], over the last six months, there has been a division within those who stayed: between those who say “we won’t leave because we will rebuild the country” (“someone has to work”), and those who could not articulate a soothing narrative about why they have stayed.”

How those who left differ from those who stayed

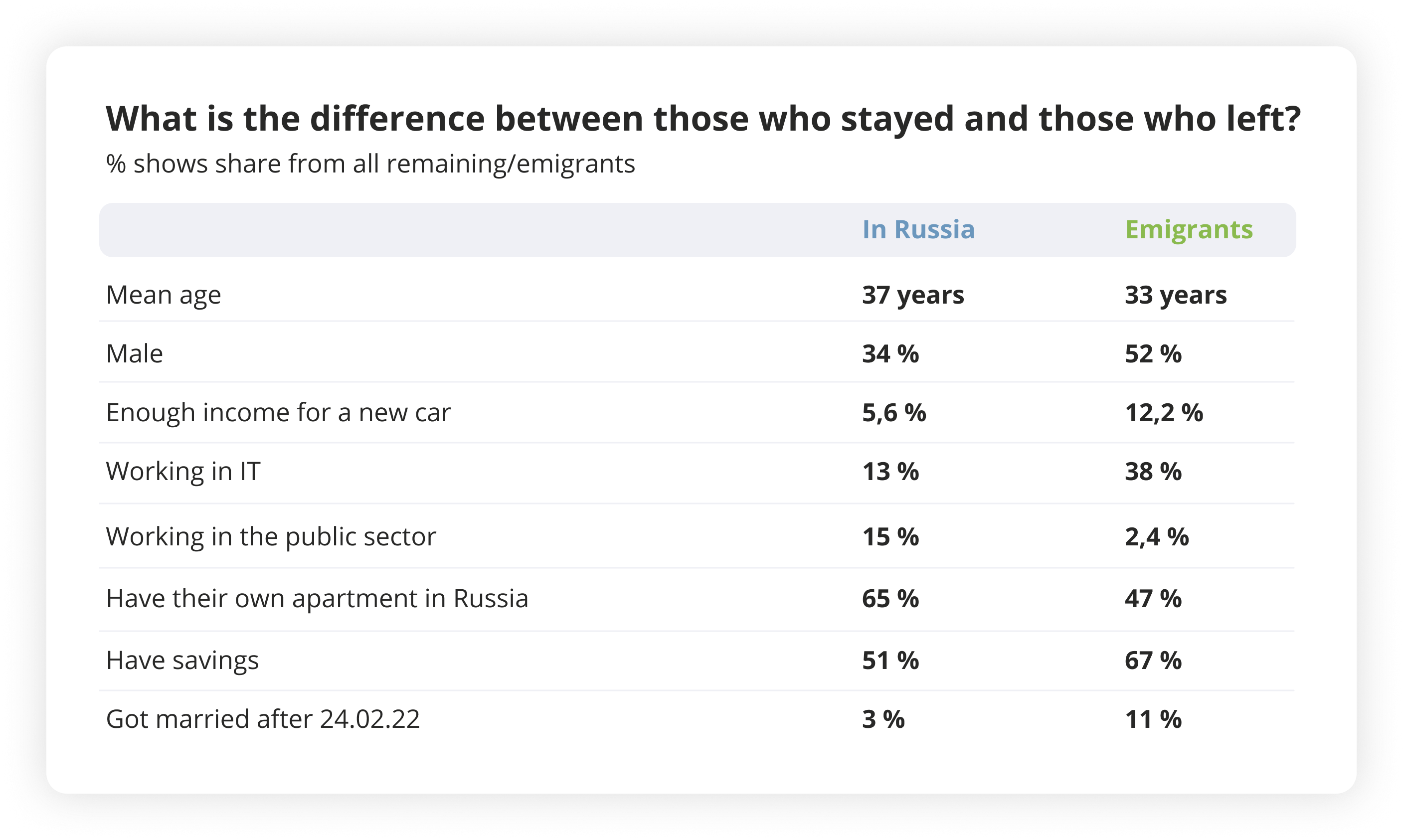

Conclusion: those who left are wealthier and there are more men among them. Those who stayed often have their own apartment.

Our study allows us to compare those who stayed in Russia and those who left based on socio-demographic parameters and the impact of the year of war and economic crisis on them.

The data we collected confirms the common belief that on average, those who left are wealthier, with a significantly higher representation of IT specialists and men. Those who left are also slightly younger than those who stayed.

The table below shows the differences that are statistically significant, meaning that it is not a random, but a consistent distribution of responses.

Margareta Zavadskaya says:

- “Having high income is an important predictor of emigration. The predominance of males also indicates economic privileges: IT specialists are more likely to be men and have higher salaries.”

Among those who stayed, there is a higher proportion of public sector workers. “This indirectly indicates a loyal middle class whose income depends on the state,” explains Zavadskaia. In addition, an important characteristic of those who stayed is owning an apartment in Russia: 65% of those who did not leave own accommodation, compared to just 47% of emigrants.

There are no significant differences between those who left and those who stayed in terms of education level or having children.

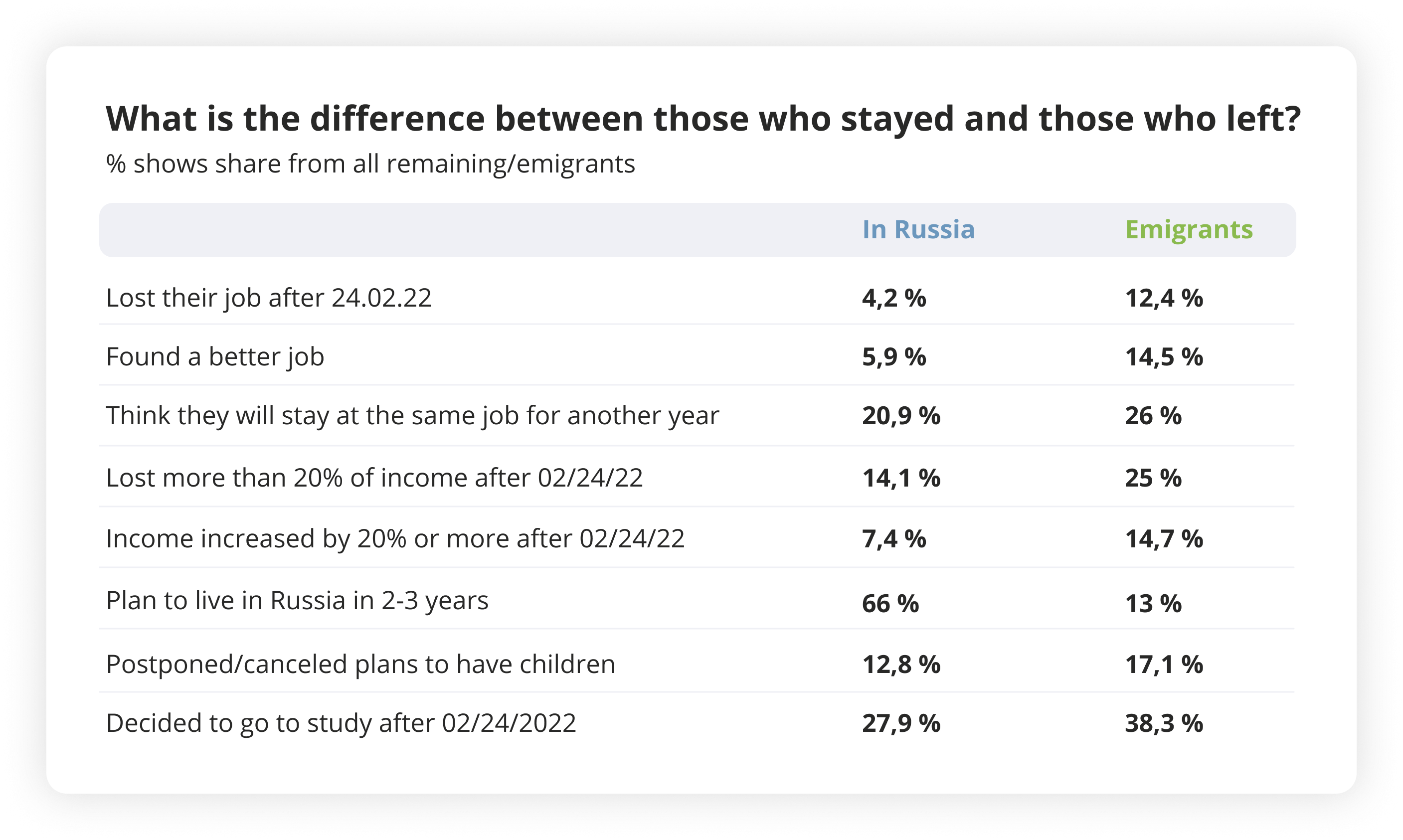

Conclusion: Those who emigrated experienced more changes in their personal and professional lives.

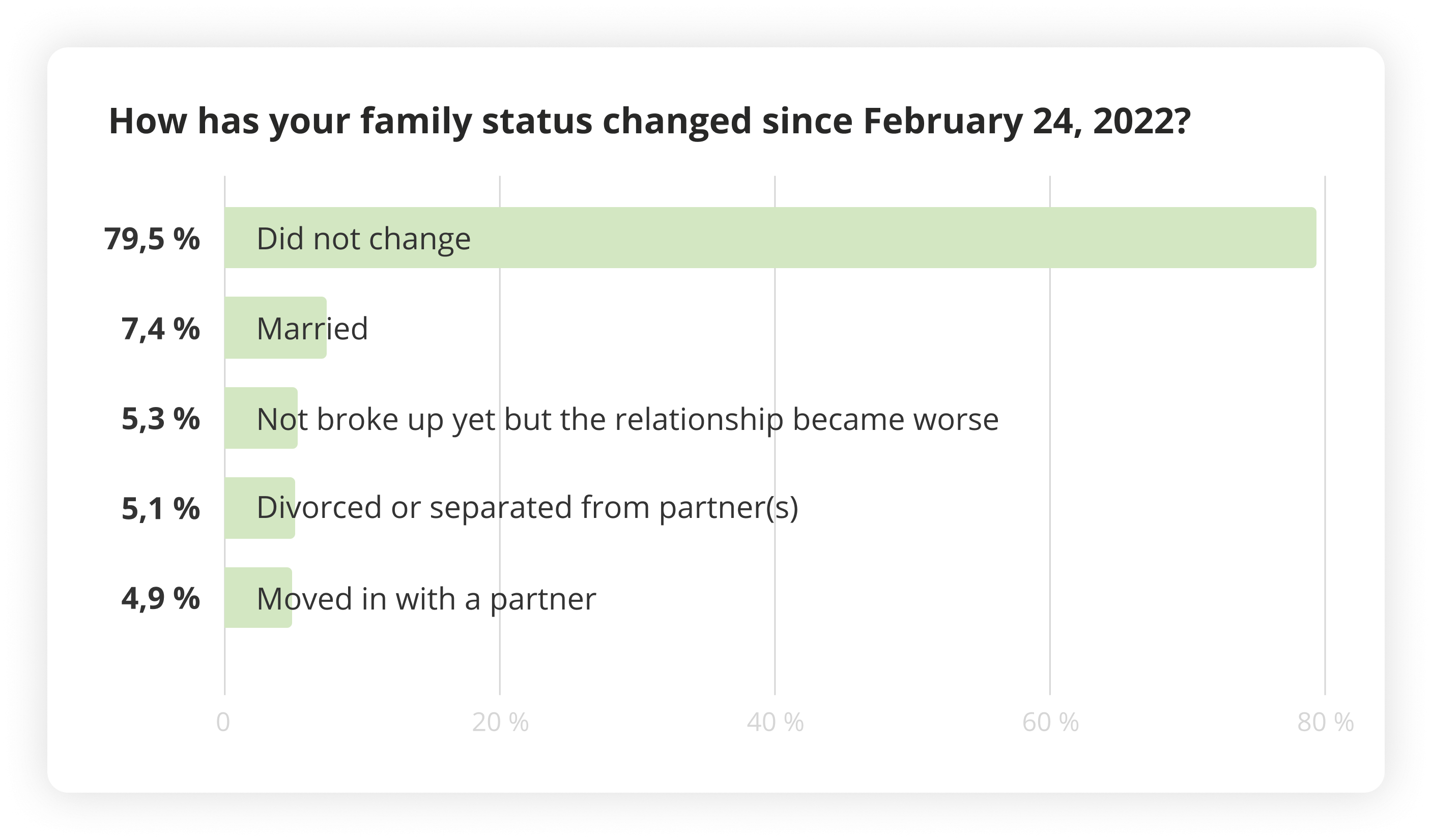

Although new immigrants are on average wealthier, they suffered more losses in 2022. Overall, they experienced more changes: they more frequently got married (which can be easily explained by the need to apply for documents for departure together), moved in with partners more often (also due to joint emigration), lost jobs more often and found more suitable ones.

Margarita Zavadskaia says:

- Many employers simply fired such employees [who left], sometimes people left because they did not want to pay non-resident tax or finance the military operation, in addition to having difficulties with using their Russian salaries.

Meanwhile, a larger portion of those who have emigrated are confident that they will stay in their current jobs for at least another year – this is what 26% of emigrants and 21% of those staying believe. In other words, respondents assess the risks of losing their job or business in Russia in 2023 as very high.

A third of emigrants said they have gone or are planning to go back to school — either to change their profession or to improve their qualifications.

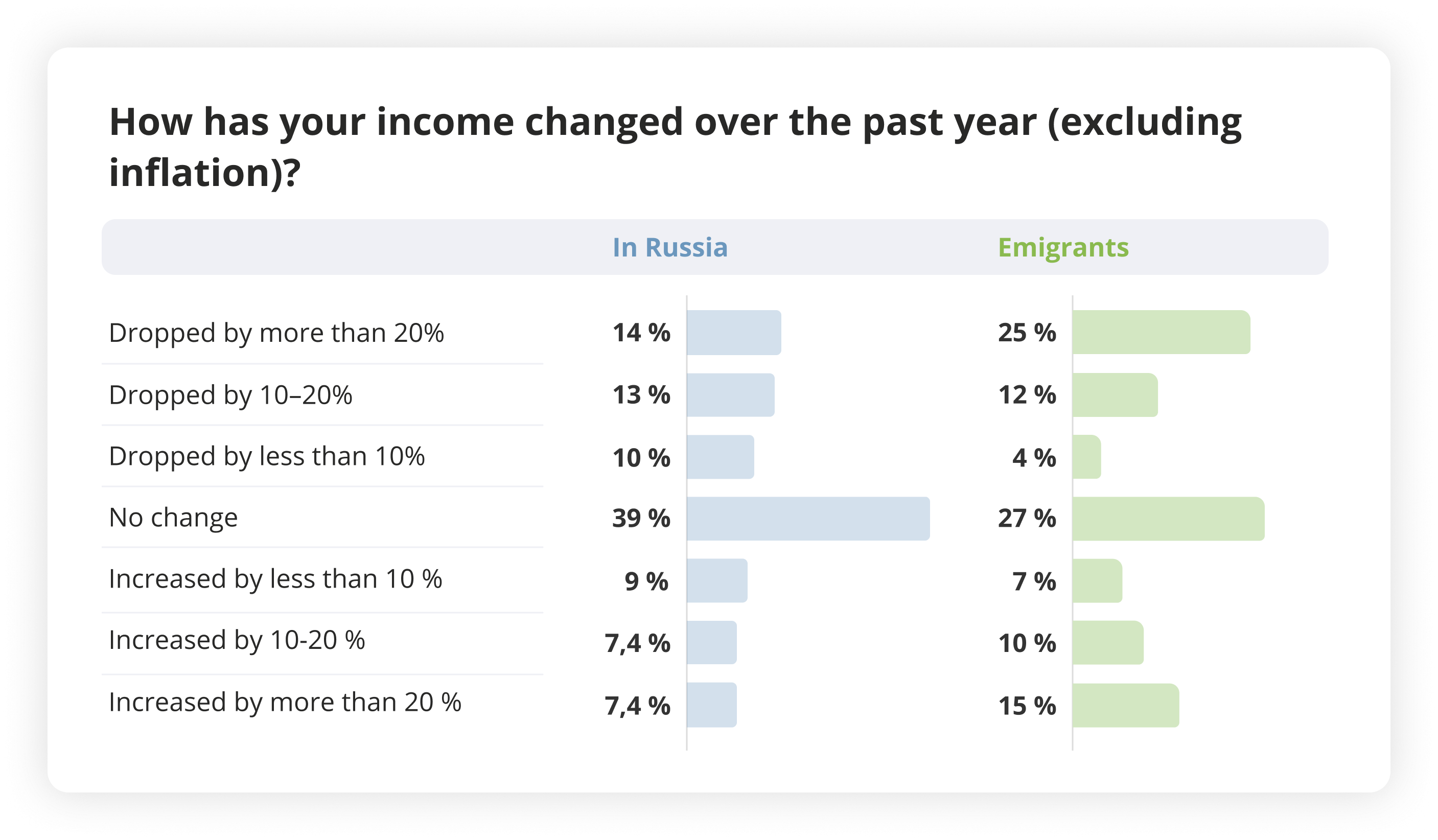

Interestingly, the share of those who lost a significant portion of their income and those who are having a better income are both higher among emigrants.

According to the researchers from OutRush, the income losses among emigrants are even higher than what our data suggests. However, they also took more actions to compensate for the losses, according to our research. In comparison to those staying, in 2022, more emigrants found higher-paying jobs (15% of those who left and 6% of those who stayed). Additionally, emigrants more often reported that new opportunities emerged in their work after February 24, 2022 (12% of those who left and 8% of those who stayed).

Why do some people emigrate while others do not

Conclusion: The remaining often not only negatively evaluate the situation in the country, but also suffer from it.

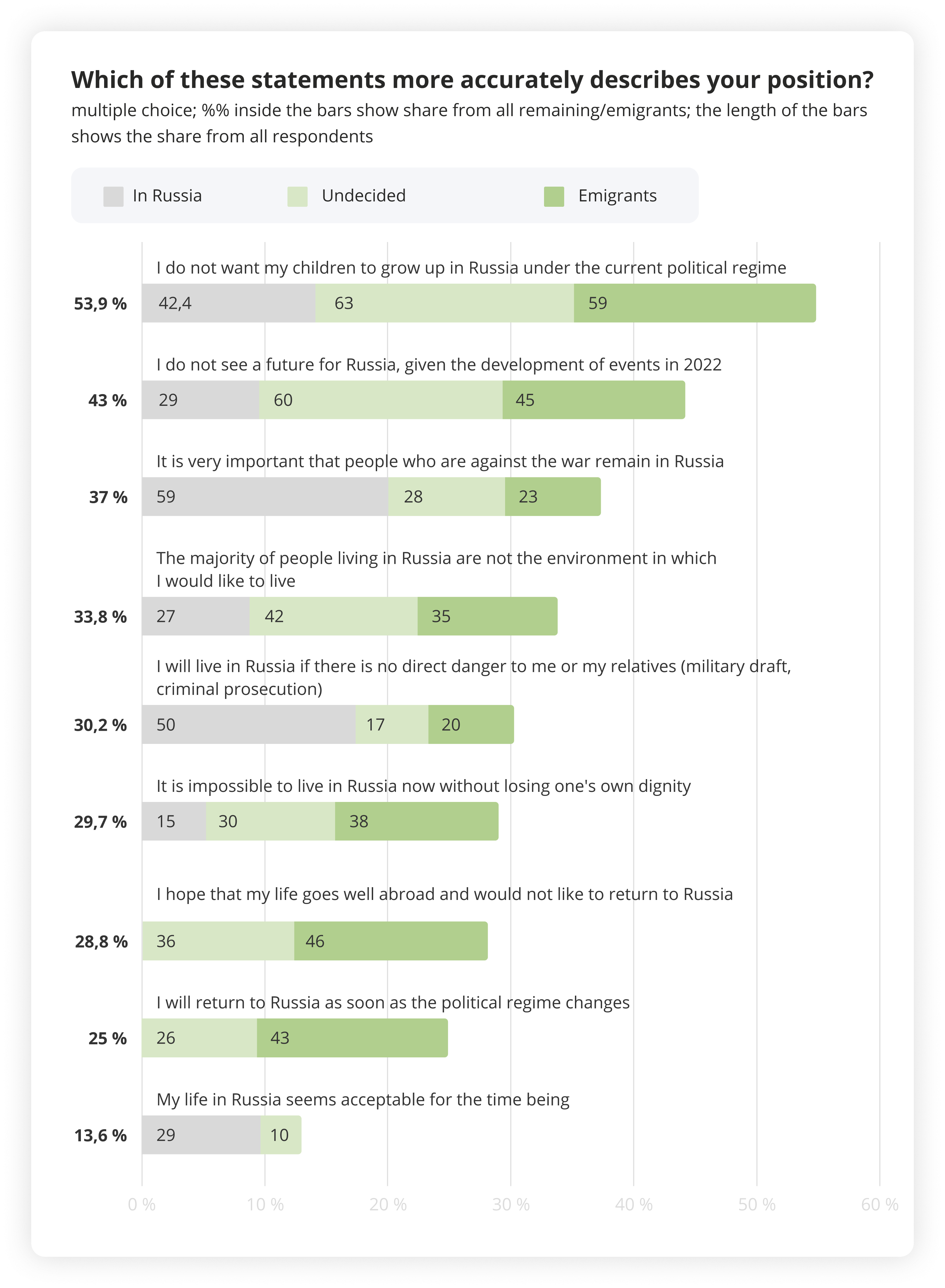

To understand why some people emigrate and others do not, we tried to compare those who stayed and those who left in terms of their values and views. In order to do this, we asked respondents to choose from a list of statements with which they agree.

The differences in the choice of statements turned out to be very significant. But the most surprising thing is that among those who stayed, a high proportion of people negatively evaluate the situation in the country and suffer from it. More than a quarter of those who stayed (28%) said that they do not want their children to grow up in Russia under the current political system.

15% of those who stayed agree that it is currently impossible to live in Russia without losing their dignity – and among those who previously said that they chose to stay in Russia voluntarily, only 7% support this statement.

Among those who stayed, only 29% agreed that their life in Russia seems acceptable for now. Among the undecided, only one in ten think so.

Margarita Zavadskaya says:

- As for the statement “I don’t want my children to grow up under the current regime”, we [Paperpaper.ru and OutRush] have similar results. Children have been a decisive factor for many families [in their decision to emigrate].

27% of those who stayed and 35% of emigrants agreed that “most of the people who stay in Russia are not the kind of environment in which I would like to live.” “It is noteworthy that the difference [between those who stayed and emigrated] is not that big,” comments Zavadskaya. A significant portion of respondents, both in Russia and abroad, currently have a negative opinion of most Russians.

Who is planning to live in Russia

Conclusion: Almost half of the emigrants want to return to Russia after a change of regime. However, only 13% believe that this will happen quickly.

One of the main questions in the survey is whether readers of independent media plan to live in Russia in a few years. 41% of those surveyed plan to be in Russia within a year — 12% definitely and 29% with some doubt.

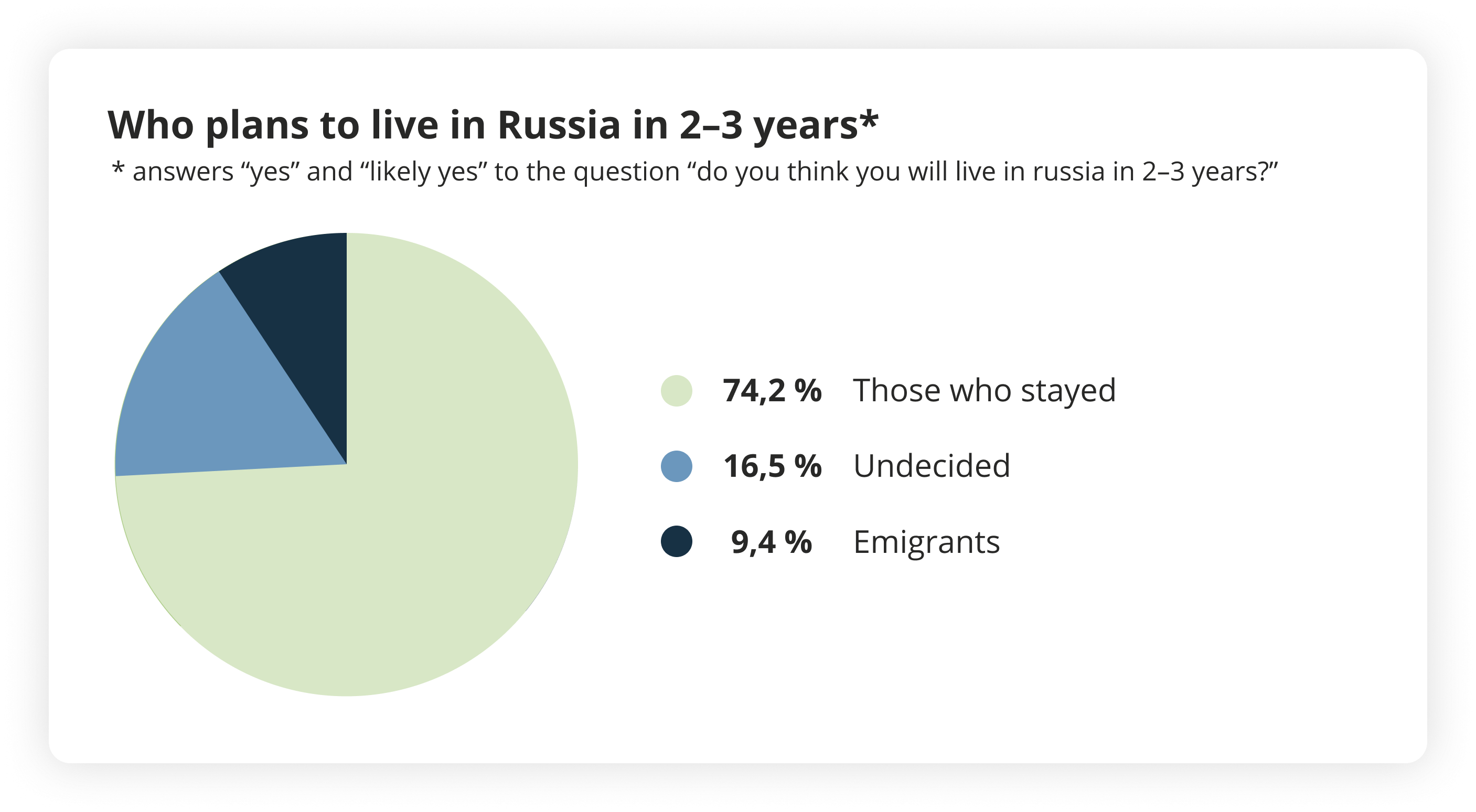

Fewer readers plan to live in Russia in 2–3 years: 32% (and only 8.2% are certain about it).

We calculated the share of those who stayed, those who are undecided, and those who emigrated, among the respondents who associate their future with Russia. It turned out that three-quarters of this group are made up of those who continue to live in Russia now.

Almost 13% of those who left are planning to return soon. From the answers to another question, we know that 43% of emigrants declare that they will return as soon as the political regime in Russia changes. This means that only a small part of those who responded believe that this will happen in the next 2–3 years.

“According to our data, those who left are very unlikely to return,” adds Margarita Zavatskaya. “Currently, less than 3% have come back.”

The data from Paperpaper.ru also shows that about 8% of those who remain in Russia are unlikely to live there in a couple of years, and 26% find it difficult to answer this question.

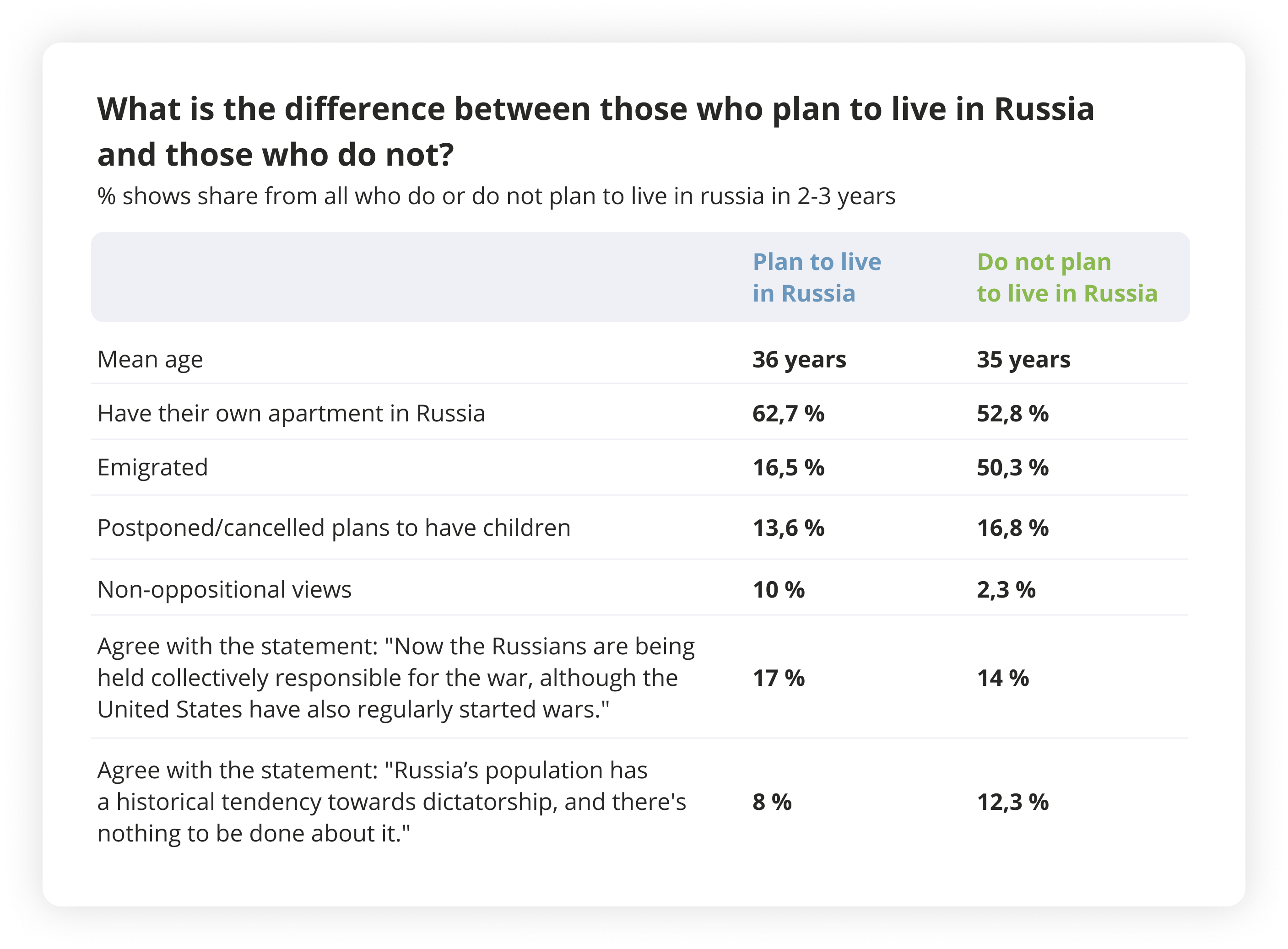

Conclusion: Those who have their own apartment are more likely to want to live in Russia in the next few years. Age and education do not play a role.

Plans to live in Russia in 2–3 years are much less dependent on the respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics than the choice between emigration and staying in 2022.

Those who plan to live in Russia are almost the same age as those who are not ready for this. Gender and education level do not play a role in this question, nor does having close friends in Russia (which almost all respondents do). Statistically significant differences are based on the ownership of their own apartment in Russia.

Conclusion: People with oppositional views are less likely to see their future in Russia. However, few in either group agree that Russians are politically hopeless.

Another pattern emerges: those who connect their immediate future with Russia are less likely to have oppositional views. On average, among all respondents, 93% agreed with the statement “I am against the policies of the current leadership of Russia.” However, among those planning to live in the country, a larger portion agreed with the statements “I am satisfied with the political situation in Russia,” “Until February 24, 2022, I was generally satisfied with the political situation in Russia,” “I am generally opposed to the policies of Russia’s current leadership, but I believe that there is no better alternative to Putin,” and “I am not interested in politics.”

Few in either group agreed with the statement that “the population of Russia has a historical tendency towards dictatorship.” That is, the reason why emigrants and some who stay do not want to live in Russia is not that they consider the country’s inhabitants politically hopeless, predisposed to a “slave mentality.”

Among the survey participants, there are also no differences in the degree of anti-Americanism when comparing those who have left with those who have stayed and those who are planning their lives in Russia with those who are not, notes Zavadskaya.

What are the readers’ plans for children and money

Conclusion: The savings of every third reader are in foreign banks. 3% have sold their apartments in Russia.

To assess how radically readers are severing ties with Russia and taking care of their future, we asked about their plans for savings, property, and children.

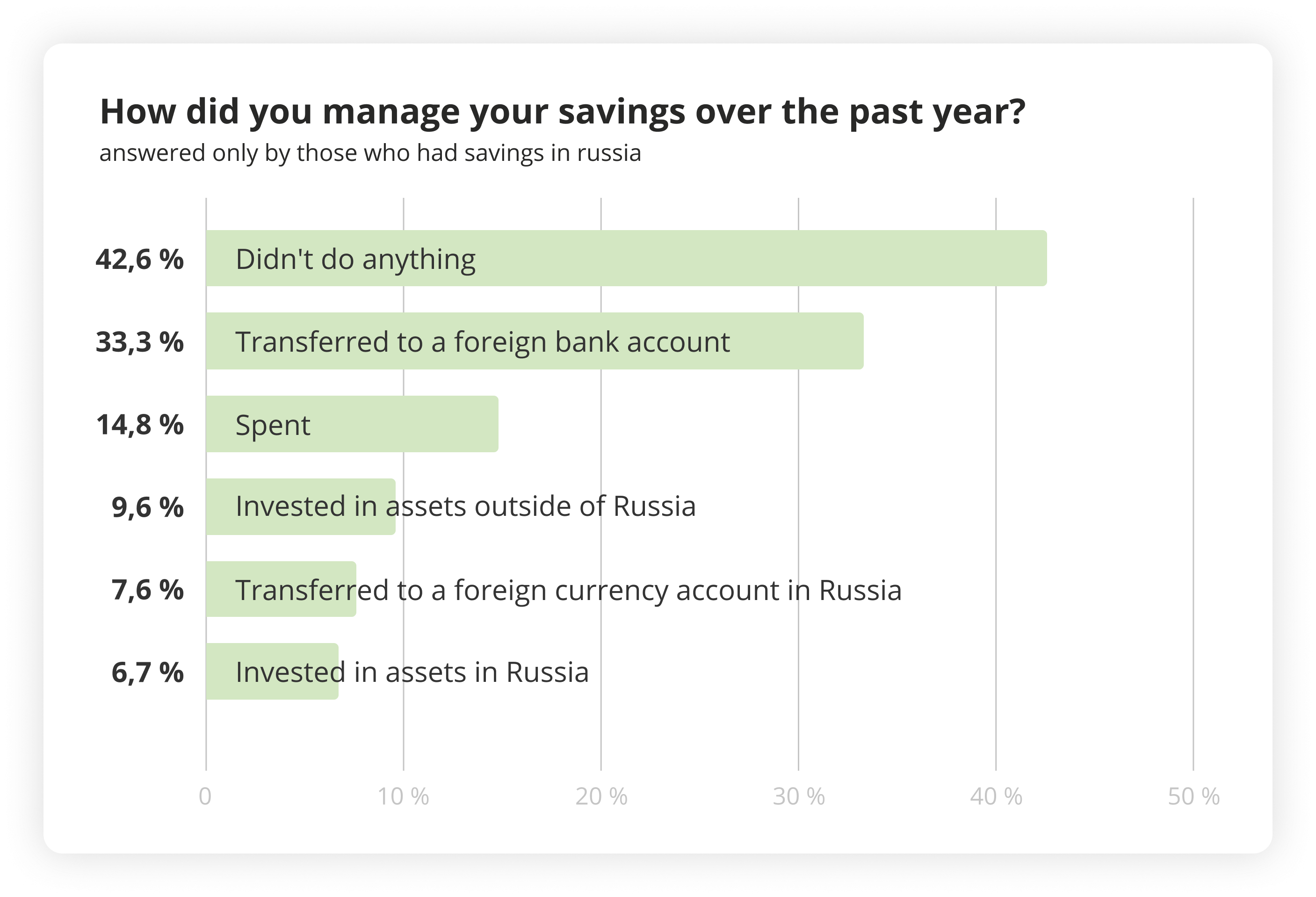

57% of respondents reported having savings. Of those, one-third transferred their money to a foreign bank account, and one-tenth invested in real estate or other assets abroad. 7% of those readers who had money invested it in Russian assets. Of those who invested in Russia, only two-thirds plan to live there in 2-3 years.

More than half of the respondents have their own apartment in Russia, and another 10% have a mortgage. After the start of the war, 3% of readers sold their apartment, and 18% plan to do so. 7.2% plan to buy property in Russia (a third of these readers do not plan to live in Russia in 2-3 years).

Conclusion: 16% of readers have postponed plans to have children. 10% of readers reported deteriorated relationships with their partners due to the war.

Emigrants more often than those who stayed have refused plans to have children. Overall, 16% of readers postponed or canceled such plans, while 10% kept them.

Margherita Zavadskaya says:

- “The answers regarding savings and plans show that readers are still hesitating, and not everyone has made a final decision.”

The year of the war became a serious test for relationships in couples. Against the backdrop of an increased number of marriages among emigrants, one in ten readers reported that their relationships with their partners had worsened or broken down.

External factors had the greatest impact on relationships, with almost a third of respondents reporting that the issue of emigration had affected them. Many noted an ideological closeness, which helped some readers found suitable partners.

Overall, the survey showed a high degree of uncertainty in planning. It is possible that over time, readers of Russian independent media will become less pessimistic about the future of Russia.

Margherita Zavadskaya says:

- “Results of the survey among Paperpaper.ru readers and other independent media are, of course, insufficient to draw conclusions about all those who have left and the entire population of Russia. However, these are very important data reflecting the moods and plans of a well-educated and opposition-minded audience. These data show us some very important nuances in the attitudes of those who have stayed and those who have left.

- First of all, we see that the survey audience consists more and more of people leaving the country and people who have survived the move relatively well in economic terms, even compared to all emigrants.

- Secondly, we observe a growing distance, if not alienation, of emigrants from those who have stayed. Either the readership is moving abroad, or readers are increasingly less willing to stay in Russia. I lean towards the first interpretation of the figures obtained.

- Thirdly, I want to draw attention to the motivations of those who stay: the need to rebuild the country, the importance of being in their homeland in a difficult moment, and maintaining faith in the future. Among emigrants, the rhetoric of maintaining dignity and the absence of faith in the country’s future predictably dominate (in fact, the very fact of leaving speaks to that).”